Ever since the Eurozone debt crisis started some 18 months ago, the policy makers (the troika comprising the IMF, ECB and European Commission) have consistently failed to implement measures that could provide a comprehensive solution. Decision making has been always been reactive rather than proactive and been characterised by what has become know as ‘the sticking plaster approach' whereby enough is done to cover the wound in the short term before it reopens again and another palliative is applied.

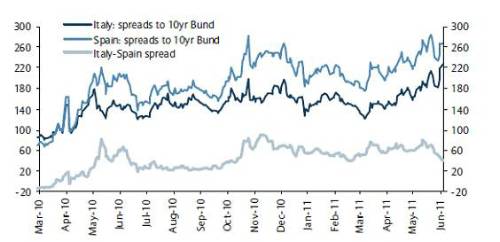

Essentially, the troika has adopted a liquidity based approach at providing sufficient funds to cover funding needs while neglecting the underlying problem of solvency. However, as the crisis has deepened with more countries affected requiring larger bailouts, it has become increasingly expensive and difficult to kick the can down the road anymore. In the last fortnight since Greece narrowly agreed to an amended austerity package in return for a second bailout, the bond markets have lost patience and contagion has spread to Italy and Spain (see chart below), both of which are too big for the Eurozone to save.

With the Eurozone ministers looking over a precipice at the meeting yesterday they knew they had to put their difference aside and collectively agree a change in strategy or risk the demise of the Eurozone and, possibly, the Euro itself. In this respect, for the first time, they stepped up to the plate, and took some necessary but not sufficient measures to save the Eurozone project. This is welcome and should provide some short term relief to markets but as the note will argue more is necessary in order to yield a permanent resolution to the crisis.

What was agreed at the summit

The main points agreed are summarised below:

Greece

-

A new €109bn bailout that will include participation from both IMF and, crucially, €37bn from the private sector through banks and other private sector lenders.

-

The period of repayment for the bailouts is doubled from 7.5 to 15 years.

-

The interest rate is cut substantially from 5% to 3.5%

-

There will be an extension of maturity for Greek bonds of up to 30 years

-

A ‘Marshall Plan' is to be implemented to help promote growth and employment in Greece. One of the main problems with the initial bailout and austerity package is that the measures to cut the deficit had not been implemented problem because of endemic structural flaws and widespread corruption etc.

Portugal and Ireland

Private Sector Involvement (for Greek debt)

The section on PSI is complicated and not entirely clear but the private sector will become involved through a combination of measures that include a debt buy-back programme at a discount to par and extension of maturities of the bonds of up to 30 years. The extent of the PSI depends on its voluntary participation but the authorities expect some 90% take up. If that is the case this should provide PSI of about €135bn in the period of 2011-20. A list of financial institutions indicating support is given.

For those interested in more detail of PSI, the programme involves an exchange of Greek bonds into a combination of 4 instruments as well as a debt buyback facility (the size of which is unknown). The 4 instruments are:

-

a par bond exchange into a 30 year instrument

-

a par bond offer involving rolling over bonds into 30 year instruments

-

a discount bond exchange into a 30 year instrument

-

a discount bond exchange into a15 year instrument

The principal of the first 3 options is fully collateralised by a 30 year zero coupon AAA bond and the last option is partially collateralised. All of them are priced to produce a 21% loss in NPV.

European Finance and Stability Fund (EFSF)

The fund has been given extra flexibility and powers

-

To make precautionary loans to prevent countries reaching crisis point. This is designed to be pre-emptive and is a more flexible form of credit

-

The power to buy bonds in the secondary (open) market. This will extend beyond the 3 countries that have so far received bailouts.

-

The ability to lend to Eurozone governments to help boost the capital strength of the banks. The fund has to lend to the state as it is not empowered to lend directly to the banks.

-

There is no expansion of the current €440bn lending capacity, although the statement said it will remain under review.

European Central Bank (ECB)

One of the sticking points over recent weeks has been the ECB's insistence that it would not accept Greek (or other countries) debt as collateral in the event of a default, even if the default was temporary or selective. Importantly, the ECB has backed down on this hard-line stance and will now accept Greek bonds as collateral after default on the basis that the bank is given guarantees from the EFSF on sovereign bonds pledged as collateral.

Comment on measures agreed

While the proposals are not a silver bullet or panacea for the debt crisis they are a considerable step forward. For the first time since the crisis erupted in the Spring of 2010 the authorities have been pro-active and, at least partially, addressed the issue of solvency and not just liquidity driven financing needs. Once again, when looking over the edge of the precipice the troika has decided to step back to save the Eurozone. The difference this time was that the stakes were much higher to more radical measures were demanded.

The deal represents a volte face for Germany in particular that Mrs Merkel might find difficult to sell to the domestic Parliament and the electorate. She should be applauded for having the courage to take such a leap. The Eurozone has taken the first significant steps to becoming a fiscal and political union as well as a monetary union. This is a necessary condition for a monetary union to function effectively in a region where the economies are so diverse (Greece and Germany being the 2 extremes) such as the Eurozone. Indeed, President Sarkozy of France described the new powers afforded to the EFSF as ‘'the beginnings of a European Monetary Fund''.

To achieve full fiscal union there is still some way to go but the Eurozone has taken the most important step of recognising that each country must sacrifice some economic sovereignty for it to be viable in the long-term. Ultimately, the EFSF might well become the EMF and there could be one central Treasury deciding common fiscal policies (e.g. tax rates). This may also involve the collectivisation of debts into a common European bond or bonds issued by the new EMF to swap for bonds from the weaker peripheral countries (a variation of the Brady bond solution used in Latin America in the 1980's and 90's). However, it would be churlish to have expected the authorities to have proposed such radical measures at this stage as they would not have been acceptable politically; instead, they should be congratulated on going as far or even slightly further than could have been reasonably expected.

Turning to the existing proposals there are issues that arise that will have to be addressed and dealt with in the short term, the most important of which are as follows:

-

The participation of the private sector will almost certainly entail a default from one or more of the credit rating agencies as have been indicated by S&P already. This may be a selective or temporary default (for only a few days) but is important because it could trigger CDS on Greek debt and force the banks to write down the value of debt, possibly to zero, in their balance sheets. A selective default is where a rating is assigned when a borrower misses a payment on a specific bond but continues to service its other debts.. The big banks with the largest exposure are BNP, Societe Generale, Commerzbank and Deutsche Bank.

-

The greater powers granted to the EFSF will require extra capital eventually. However, there has been no increase in the resources of the fund. This is a disappointing and surprising omission given how significant the empowerment of the fund has now become. There is no point in giving it extra firepower if it cannot use it. If contagion in Spain and Italy resumes it will certainly require more resources than is currently available.

-

The changes to the EFSF will require individual Parliamentary approval in the member countries. While this should not be a problem it will take some time to achieve for all 27 members of the EU and could lead to an unwanted delay in the new measures being put into effect, especially if there is a period of uncertainty and contagion before it can act.

-

There will still be considerable domestic resistance for the new proposals in the core countries and not just in Germany. The Eurozone has taken big steps to becoming a transfer union and the electorate in Germany especially were promised this would never happen. There is a constitutional challenge in the German courts to the legality of the bailouts and the result, due in September, will be eagerly awaited.

-

While the size of the bailout to Greece is substantial and the country gets debt relief through the PSI and improved terms, the effect of the debt to GDP ratios will not be sufficient, in my view, to allow Greece to return to a debt sustainability path and stable economic growth. Much will depend on how effective the new ‘Marshall Plan' is but it is likely that the debt/GDP ratio will still be over 100% for several years unless there is a global economic boom. Portugal will also benefit from the improved bailout terms but it will still, I believe, require a second bailout. Ireland has a much better chance of avoiding a second bailout. It is more competitive and has a much larger export sector; it has also taken deeper austerity measures and so is already on a better footing.

-

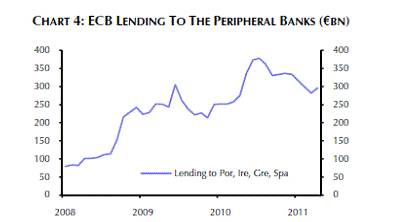

The ECB has greater flexibility to pursue an independent monetary policy. In the past the ECB had been buying periphery bonds in the open market but it was always a very reluctant purchaser and had stopped buying in recent months, doing nothing to arrest the contagion to Spain and Italy. Now it can concentrate on its monetary policy it will have the green light to raise interest rates further to the detriment of the weaker periphery economies. It has lent increasing money to the periphery banks (see chart) as emergency funding and is keen to reduce this.

As one can see there are several outstanding issues from the current proposals of which the issue of default is the most pressing and urgent. We will, no doubt, hear from the rating agencies soon and it will be interesting to see what they decide and what the ramifications are. At least, the authorities have now accepted a default as inevitable and measure have been taken to make sure the Greek banks, that are most vulnerable in the event of default, will still have access to capital through the Eurosystem liquidity operation. The measures are a real restructuring so a default is right and proper but it is also a good thing that markets should react positively to if it is managed in a controlled way. I think the proposals outlined in the summit achieve that. Furthermore, the stress tests of the 91 European banks announced last Friday reveal there is limited CDS exposure in their balance sheets. Apart from the Greek banks the hit to the balance sheet and earnings from the implications of a default are limited and the important point is whether it leads to destructive contagion and seizes up the Euro banking system (as happened after Lehman's demise); again the measures taken yesterday should forestall such fears.

Overall the proposals from the summit are a substantial and important step towards fiscal union and integration that is necessary to achieve a comprehensive and permanent solution. The measures are still too liquidity driven but the issue of solvency is at last addressed and there is significant debt relief for Greece and the other peripheries. Although the proposed measures should function well once passed by the respective Parliaments they need to be more scalable and this will become evident over time as it becomes clear that the size of the debt in the periphery economies remains at dangerous levels. Furthermore, there is increasing evidence of a slowdown the Eurozone economies, including Germany and other core countries, so the lack of growth will make it more difficult. The summit has achieved the goal of providing a necessary change in strategy but will not be sufficient to prevent further crisis episodes in future. What is has demonstrated is that the Eurozone politicians have the political will to save the Euro project and the currency and I continue to believe they will do what is necessary in the future.

|