By Alex White, Head of ALM Research, Redington

This is not an exhaustive list of pros and cons. There are plenty of other factors, not least timing, spreads are at around their 25th percentile lowest historically, so now is a more expensive time to do typical CDI than 75% of history.

This is merely highlights one of the biggest weaknesses of CDI, that unexpected cashflows are often much larger than expected ones.

While liability and credit cashflows are pretty certain, they’re not the only cashflow requirements schemes have to contend with. And, unfortunately, unknown cashflows are often bigger than the known ones. Put another way, the payments you don’t expect are often bigger than the ones you do.

What do the numbers say?

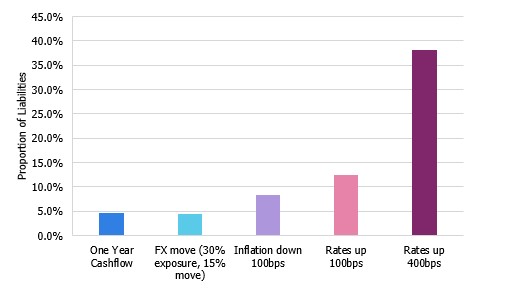

Take a representative well-funded, well-hedged, closed DB scheme. It’s likely to have a duration around 13 on gilts +50 and pay out 4.5-5% of the value of its liabilities each year.

Only well-funded schemes can afford CDI, so let’s simplify the calculations, and assume the scheme is fully funded and fully hedged.

If the scheme invests entirely in Sterling credit and LDI, then it has no direct FX risk. However, this does introduce some unpleasant tail and concentration risks - the Sterling IG market is around £400bn, compared to c£1.2 trillion of DB schemes.

Even ignoring insurance companies, that’s a hugely imbalanced supply and demand, meaning both that the assets are likely overpriced, and that in a downside event everyone will be trying to sell the same assets. We had a glimpse of this with the gilt crisis in 2022.

So, the scheme diversifies into global corporate bonds, which potentially means a large USD exposure - let’s say the portfolio is 40% LDI, 30% GBP IG, 30% USD IG, hedged to GBP.

A 15% move in the FX rate would create a cashflow requirement the same size as the liability payments. For context, we saw that size move on the day of the Brexit vote.

Inflation is bigger still - if inflation falls, the hedge will be out of the money. If inflation falls by 1%, the scheme would have a cash requirement 1.5-2x as large as the expected liability payment.

And then there’s interest rates

If interest rates move up 1%, the scheme would lose around 13% of its assets. The liability PV would also fall, but the cash would still be needed.

Rates moved nearly 4% over 2022, which would equate to around 40% of the PV, totally swamping the expected, neatly mapped out liability cashflows . And a 100bp move is pretty likely over any year- historically it happens about 10% of the time.

A 35bp move leads to a change in PV about the same size as the annual benefit payment - that happens over a year more than ¼ of the time.

While CDI has a lot of advantages, it is crucial to think through these risks and make sure any implementation of CDI is robust to them.

In particular, unexpected cashflow requirements are often much larger than expected ones.

|