By Alex White, Head of ALM Research, Redington

For students living away from home and studying outside London, this is capped at £8,700. Interest is charged at RPI plus a spread which rises with income up to 3%, and payments are taken as 9% of the portion of salary above a threshold (currently 25,725). Loans are written off after 30 years. The thresholds rise at RPI + 1.6% each year.

Looking at the structure, there is a lot about it that is well designed, and the goals of the design are fairly clear. Payment amounts are means-based, so low earners are not forced to make huge payments, and no-one pays more than they can afford. The interest charged is also means-tested, which implies a desire not to charge punitive interest to low earners. But does it work?

As often in finance, the question comes down to what might be an appropriate discount rate. There’s not an obvious choice, but we could start with 95% LTV mortgage rates, on the grounds that this will be a similar demographic. At around 2.5% fixed, these are roughly gilts + 1.5%. This is secured lending to the richer end of the market, so would be a lower bound. Broad market BBB-BB spreads are around 80, so we may want to add that. We would also want to factor in the complex optionality within the payment structure, so we might say gilts plus 3% is a vaguely sensible rate in the current market.

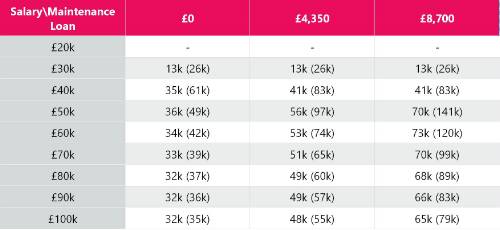

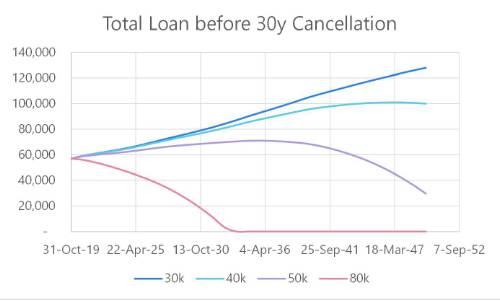

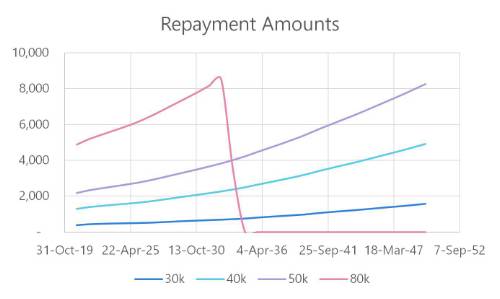

So what happens? For different salaries, I assumed increases of RPI + 1.6%, in line with the long-term rate used to increase the salary thresholds. I then made some simplifications around payment timings, and projected the loan of a graduate starting now, having just completed a 3y course, and earning different amounts, and worked out the PV of their total payments. In all cases there are no overpayments. While many of these are unlikely to be graduate salaries, the same effect will occur if salaries reach these levels a few years into graduates’ careers. The results are below.

PV of payments on Gilts + 3% (total undiscounted payments)

What we see is a slightly bizarre effect. Anyone earning below the threshold pays nothing, and lower earners benefit greatly from this floor. Very high earners can afford to pay off the loan faster than it accrues interest. Those in the middle, however, can expect to make large payments of several thousand pounds per year, while seeing their loan grow faster than they can pay it off. This means they end up paying a lot more than higher earners- the middle does get squeezed. Regardless of political views, it’s unlikely that this was an intentional aspect of the design

|