And in the next 18 months there is a reasonable chance both of his becoming President again, and of his being in prison (for several reasons, among them attempting to overthrow democracy through violence).

This seemed worth investigating, for several reasons:

• Data on coups should be relatively easy to obtain

• It’s not an obviously terrible first order approximation for more nebulous ideas like instability and expectations of democracy more globally (though with big caveats- e.g. the size of the country might matter a great deal)

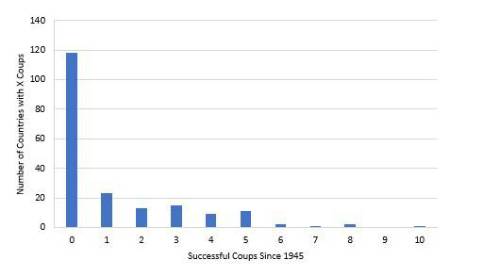

The first apposite fact about coups is that one coup seems to make further coups more likely. This is unsurprising- if no-one expects the law to be upheld, it’s much harder to oppose violence effectively. And we can see it in the data - if coups were distributed randomly with an equal probability in each country (with a probability of a coup of roughly 1.5% per country per year), even allowing for years with multiple coups the chance of any country having seven coups would only be around 5%. Argentina has had seven, Syria and Bolivia eight, (<1% chance) and Thailand 10 successful coups. So coups create more coups.

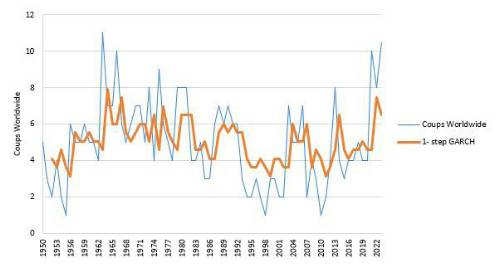

This suggests that, globally too, we should see some persistence. That is, the rate may trend up or down, but the number of coups is highly unlikely to be a Markov process. Instead, it will be better captured by a regime model, with a changing probability through time. Using a simpler data set from 1950, split out by year , and annualising the seven coups seen from 1 January to 31 August 2023 to 10.5 over the year, we see the same phenomenon. There is no clear trend, but very strong (46%) year on year autocorrelation, and a one-step GARCH model captures a fair degree of the variance (the two-step model is very similar to the one-step model here), though still potentially understating the “regime” effect.

So where does that leave us?

The very simple model (48% x number last year + 2.7 + a normal random variable with standard deviation of 2.1) is an enormous simplification, and at best it captures some rough first-order trend. But the autocorrelation means it’s probably still a better estimator than just taking the average. The model predicts 7.3 ± 2.1 coups (successful or not) next year with 68% confidence, against a long-term average of five.

That is to say, for the moment, uprisings appear to be on the rise.

|