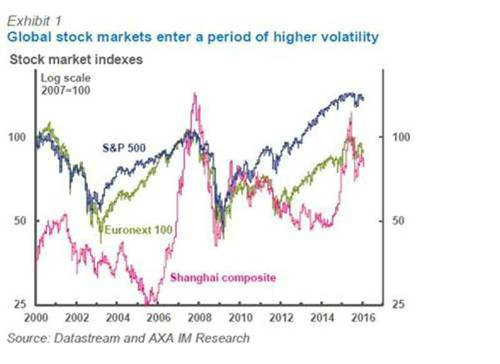

As explained in the AXA IM Research Outlook 2016, we don’t have great expectations for financial returns this year. Global growth is likely to remain sluggish, only marginally above 3%, with the equity market rally initiated in 2009 having run its course.

The very first trading day of the year was a shocker, with all the major indexes sharply down: Chinese CSI 300 -7.0%, Nikkei -3.1%, Stoxx50 -2.4% and S&P 500 -2.6%. At face value, the sell-off was triggered by the free fall of the Chinese market, which hit the authorities circuit-breaker. But what caused this latest correction in China?

The usual suspect list includes: a poor PMI (Caixin) figure in China, the expiring selling ban imposed to major shareholders by Chinese authorities during last year’s equity market rout, and the sharp rise of geopolitical tensions in the Middle East, caused by the standoff between Iran and Saudi Arabia. My colleague Aidan Yao is not convinced by Chinese idiosyncratic factors. Neither am I. For instance, the Caixin PMI edged lower to 48.2 in December, from 48.6 in November, but the predicting power of both the Caixin and the official National Bureau of Statistics PMIs has been terrible since 2012, with, for instance, industrial production growth cruising at 6.2% in November, despite both PMIs supposed to be in ‘contraction territory’. Additionally, the ban on selling is set to expire this Friday (8 January), and this has been known since its inception. Note also that high volatility could convince the Chinese regulator to uphold the ban for another couple of months.

By contrast, the tensions that have flared up between Saudi Arabia and Iran, after the execution of a Shia cleric in the former and the attack on the Saudi Embassy in the latter, is signalling the possibility of a much broader destabilisation of the whole Middle East, with potential consequences to the global economy, since these countries boast the largest crude oil (Saudi Arabia) and natural gas reserves in the world (Iran). One doesn’t have to be a doomsayer to consider a highly dangerous escalation in the conflict between the arch-rivals of the Muslim world, the Sunnis represented by Saudi Arabia and the Shias represented by Iran. A mix of conventional war, terror attacks and pitiless repression against civilian masses may set ablaze the whole region, if its leaders are caught up in an escalating spiral. Taken together, Middle East oil exporters generated 35% of world crude oil exports in 2014, which implies that, despite the emergence of shale oil and gas, the Middle East remains the largest supplier of hydrocarbons to the global economy. A large scale disruption of oil and gas supplies from the region would badly hit a weak global economy, starting with oil importing developing economies, but also oil-dependent Europe and Japan.

Strangely, oil markets barely reacted to the news, with the barrel of Brent reaching $39 before retreating to $37. Yet, the oil market is so much oversupplied that its capacity to price hypothetical developments is very limited, so long as nothing actually changes the supply/demand disequilibrium. Therefore, equity markets, which are deep, liquid and highly sensitive to risk appetite, is the place where bad news is most easily priced-in. When the overall outlook is poor, risk-on, risk-off gyrations are more likely than not. Interestingly, the US treasury market posted positive returns, although modest.

Where does this leave us in terms of equity markets? If one assumes that the worst case scenario I have outlined has a very low probability (fingers crossed), we are back to the fundamentals described by my colleague Franz Wenzel in the 2016 Outlook. In a nutshell:

• The MSCI China index is trading at low price-earnings multiples (at or below 10x), which shows that, from a pure valuation perspective, the Chinese market is attractive. Yet, its built-in volatility and the uncertainty created by official attempts to shore it up, should deter cautious investors. Trying to predict the re-rating is for only the bravest investors.

• At roughly 19x reported earnings, global stock markets trade on the expensive side, with the US market at around 20x, while Europe trades at roughly 18x, and Japan is at 16x, which argues in favour of non-US stock markets.

• Global equity markets are only slightly expensive, but a poor outlook for corporate earnings and the prospect of further US Fed tightening lends itself to, at best, a neutral rating for global equities. Yet, for those who are under-invested in the market, any significant correction might be seen as an entry point.

|