By Alex White, Head of ALM Research at Redington

But against that, value-biased investing can underperform for years, and many valuation signals effectively go too negative too early, and miss out on a lot of return. For instance, if an investor identified the dot-com bubble as a bubble in 1997 (say), they might have missed out on very strong returns for years before stock prices fell. Getting the fundamentals right doesn’t help if it takes too long for them to kick in.

It's quite common in finance to face a very plausible economic argument, with decent reasoning and a logical case, but no truly hard evidence behind it. With volatile variables such as equities this is a structurally hard problem. You might need decades to know if you’re right, by which time behaviours may have changed anyway.

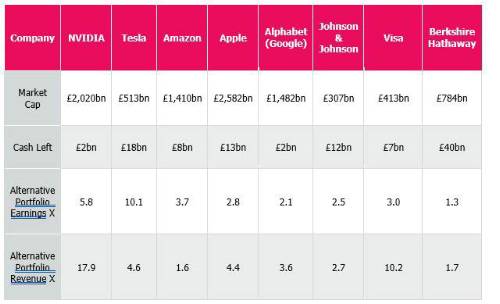

The scientific approach is to be sceptical - but that doesn’t mean these arguments can’t be at least somewhat convincing - and we may now have reached such a point with market valuations in some tech firms. Using just the 100 largest US stocks, and a very crude approach, I looked at what portfolio of stocks you could hold for the same value as one large firm, with a view to roughly maximizing the earnings on the alternative portfolio .

There are a ton of caveats here. This is only one metric, it ignores all manner of other variables, and for almost any stock it will generally be possible to make a portfolio with higher earnings. But as an illustration it helps show the spread of valuations. We show the increase you could get in earnings and what that would mean for revenue as a multiple of the larger company’s For Tesla, for example, you could buy a portfolio with 10 times the earnings and five times the revenue, with £18bn in spare change - highlighting how expensive Tesla appears on traditional metrics.

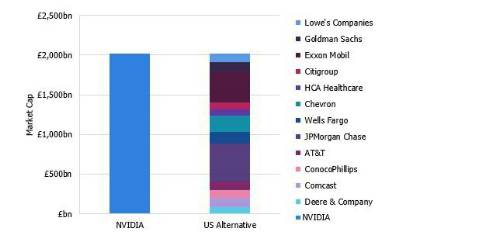

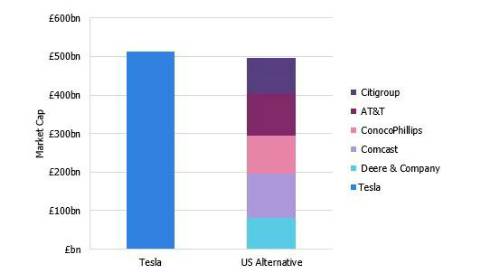

A few things come out of this, not least that within tech there is a huge dispersion of valuations. Tesla may be a bubble without Google being one, for example. But to make that more concrete, here are two of the portfolios:

Now, I often challenge arguments such as this by saying that, while the case makes intuitive sense, is there proof? Or equivalently, can you show that using the same logic in the past would have led to positive returns?

And I can’t meet my own criterion. I cannot make a track record of when I think a stock price is intuitively too high or too low. Nor can I justify why my intuitions here should be useful, and it’s not at all obvious that they would be.

Still, I find it hard to see these portfolios as equally valuable. Perhaps the better question is not whether to tilt a portfolio, but, when things look far enough out of kilter, how much or how little to bet on that. Perhaps now is a good time, as AQR would put it, to “sin a little” .

|