By Alex White, Head of ALM Research at Redington

Ok, there are the vicissitudes of the market to face, but even they are somewhat fair, in that we don’t know in advance which years will be good years – and taking more risk generally leads to higher returns.

Sadly, the reality is more nuanced. One issue I mentioned in passing in my last column is provisions for those out of work. The most obvious case is childcare, but illness or caring for sick or elderly people would also be significant drivers. Children need looking after, so it makes sense, top-down, for a system to reward it, or at least not penalize it. However, the nature of DC is the opposite.

So how big an issue is it?

Let’s consider a 20-year-old with no pot, earning £20k per annum in a 10-year lifestyle fund comprising of equities and corporate bonds, who retires at 68. They take a career break at age 30.

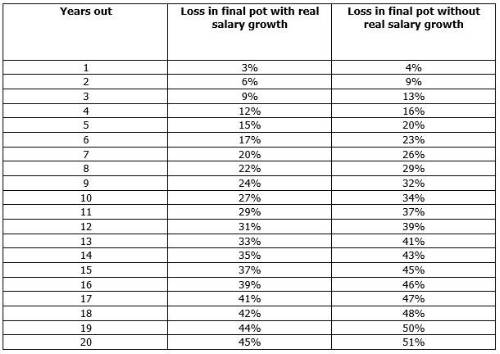

We consider two cases: one where the member’s salary continues to grow at the same real rate; and another where their salary increases with inflation but no faster – in recent times, we’ve seen wages lag inflation considerably, which would make the impacts worse. We make no allowance for other second order-effects, such as the potential for slower career progression after taking a career break.

Let’s look at the impact on the member’s final pot.

A year out is manageable, resulting in a 3-4% loss. But from there, the effect of compounding quickly runs away. A 10-year gap in a 48-year career could cost around 1/3 of the final pot, while a 20-year gap would leave the member with half as much money available. In particular, the member loses years that would have been invested more aggressively, therefore losing more than a proportionate amount of the final pot.

It probably goes without saying that, while not universally so, this is going to affect women more than men. That is, the structure of UK pensions, given how we as a society treat unpaid work, means that women, on aggregate, are likely to end up worse off in retirement than men. And while that empirical fact predates the current pensions system, the system perpetuates it. As important as infrastructure is, should policymakers be focusing the debate less around investments and more around devising a pension system that addresses this inequality?

|