Laureen Bird, Responsible Investment Analyst, Mercer Laureen Bird, Responsible Investment Analyst, Mercer

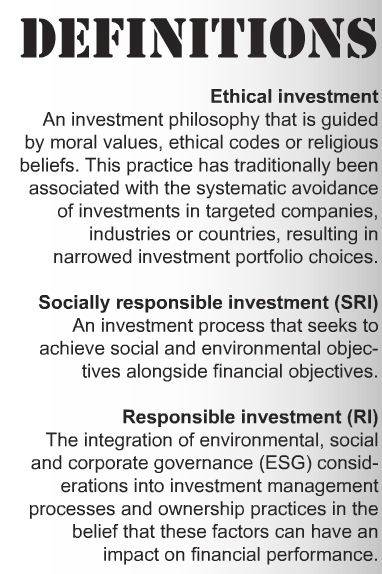

Responsible investment (RI) is often viewed with hesitation by investors due to a belief that it detracts from financial performance. This view is based on a common misconception of what RI is and how it differs from ethical and socially responsible investment (SRI). Whilst all three approaches are related, there are important differences. This article explains these differences by charting the evolution of RI from its religious roots in the 18th Century to the modern approach to RI – the integration of environmental, social and corporate governance (ESG) issues into investment decisions in order to provide better risk-adjusted returns - particularly over the long term.

Ethical investing has long historical roots dating back to the late 1700s when investors translated their religious beliefs into investment decisions by the screening of companies engaged in alcohol, gambling and tobacco. For investors with clear moral or ethical objectives this values-led approach has changed little since then – purely ethical investors still exclude so-called “sin stocks” regardless of their financial performance as a means of avoiding activities that are inconsistent with (ethical or moral) beliefs.

Fast forward to the twentieth century and ethical investment started to gain wider acceptance and an increasingly social focus thanks to the civil rights movement of the 1960s. Protests against the Vietnam War and the boycott of companies whose operations involved the production of armaments resulted in the emergence of SRI. Social issues continued to be a focal point of investment decisions for SRI investors through the 1970s and 1980s with the divestment of companies operating in South Africa, as a result of its apartheid regime. The emergence, in parallel, of the environmental movement during this period also saw environmental issues included in the issues of concern to SRI investors. Heavy industrial like extractives (oil and gas, mining) have been a particular focus of SRI investors.

Whilst SRI and ethical investors both take broader issues into consideration in their investment decisions, the key Whilst SRI and ethical investors both take broader issues into consideration in their investment decisions, the key

difference between the two is how they address the financial impact of these decisions. The ethical investor does not consider the financial repercussions of his or her exclusions. However the SRI investor aims for a balance between considering ESG issues and maintaining financial performance.

SRI investors do this by using “positive screening”, tilting a portfolio towards stocks that rate highly on specific ESG criteria (e.g. energy use, waste management, labour issues etc.). SRI investors also use shareholder activism to engage companies in dialogue on ESG issues in an effort to improve corporate behaviour.

The most recent step in the evolution of this market came in 2006 with the launch of the United Nations Principlesfor Responsible Investment (the “PRI”), an initiative that Mercer helped to develop. As of October 2012, the PRI had over 1,100 asset owners, investment managers, and professional service providers, managing in excess of US$30 trillion, as signatories. Core to the PRI initiative is the view that ESG issues can affect the performance of investment portfolios and must therefore be given appropriate consideration by investors if they are to fulfil their fiduciary (or equivalent) duty. In the UK, for example, governance and stewardship are high on the agenda, thanks to the UK Stewardship Code and the government’s focus on executive remuneration over the last 18 months.

The growth in adoption of the PRI coincided with investors dropping the “S” and describing their approach as simply “responsible investment”, an indication that issues across the ESG spectrum can be a source of risk for the investor. A note of interest is that only 15% of signatory investors categorise themselves as dedicated “ethical” or “socially responsible” investors (PRI Secretariat 2010).

The good news is that it’s not all about risk. Investors are increasingly allocating assets to sustainability/ESG-themed strategies. Opportunities are available for both passive and active investors, and across most asset classes. Environmental markets are currently an attractive area for long-term investors – these include energy efficiency; water; sustainable agriculture and timber; and waste management to name but a few. Green bonds are also a small but growing opportunity set.

An indication of the emerging interest of mainstream investors in RI is the growing body of research into ESG issues and their impact on financial performance. A recent study by RCM found that portfolios constructed based on sustainability criteria outperformed the MSCI World Equal Weighted Index across all regions. A review of over 100 academic papers by concluded that firms with strong ESG performance may now be enjoying both financial outperformance (particularly market-based) and a lower risk as measured by the cost of equity and/or debt (both loans and bonds) capital in the short run. An academic study published this year and co-authored by Elroy Dimson of London Business School, determined that successful active engagement between investors and companies on ESG issues resulted in a positive one-year excess return of up to 4.4%.

RI defines itself as the integration of ESG issues into investment decisions as a means to enhance risk-adjusted returns – particularly over the long term. RI’s focus on improving risk adjusted returns distinguishes it from the related approaches of ethical investing and SRI, of which RI is commonly misconstrued.

The launch of the PRI in 2006 and its subsequent adoption amongst the wider investment industry began the process of “mainstreaming” RI. RI can be applied across most asset classes and can be implemented by both active and passive investors. Research is emerging that supports the argument that integrating ESG factors within investment processes decreases investor risk whilst not impeding financial performance.

|