Initial commentary on these figures dubbed it a ‘Great Retirement’, suggesting that large numbers of older workers have chosen to opt out of paid work, living off their pensions, perhaps having enjoyed a slower pace of life during the Pandemic.

But new research from pensions and health experts at consultancy LCP, questions whether this is the right explanation. They point out that the latest figures show that retirement explains *none* of the increase in inactivity since the start of the Pandemic. There are actually *fewer* people of working age who are retired now than there were at the start of the Pandemic.

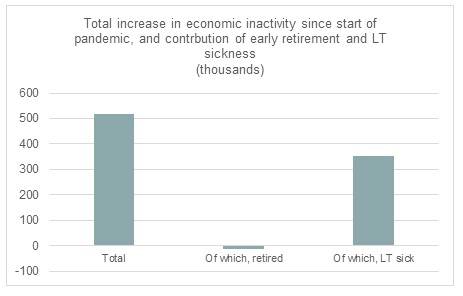

This is summarised in the chart below:

Source: ONS statistics for seasonally adjusted levels of economic inactivity. Base period is Dec 19 – Jan 20, latest data is for Oct 22 – Dec 22.

Instead, LCP point to a big rise in the number of people who are long-term sick as the key factor (see chart above), especially amongst the over 50s.

The research combines a range of data sources to understand what is going on. This includes:

• ONS Labour Force Survey data (the same source as used for the Chancellor’s figure), but focusing on ‘panel’ data which follows the same individual over time and tracks their movements into and out of economic inactivity

• DWP benefits data, both from ‘legacy’ benefits such as Employment Support Allowance (ESA) and those on Universal Credit who have ‘limited capacity for work’ on health grounds;

• NHS waiting list data for England, to see if localised pressures on NHS capacity are connected to localised increases in numbers who are economically inactive due to sickness

Key findings include:

• The growth in economic inactivity is not just about the over 50s; nearly half (45%) of the Chancellor’s 630,000 figure for the growth in inactivity relates to those aged under 50; a large part of the growth among those under 50 is in the numbers in full-time education;

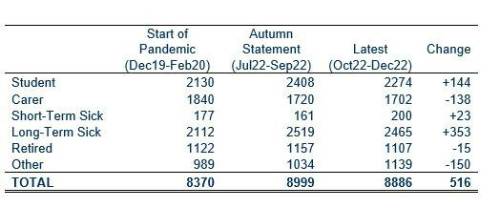

• Early retirement explains none of the increase in inactivity since the start of the Pandemic; using the same definition as the Chancellor but with the benefit of an additional three months of data, the paper finds that the increase in economic inactivity is now 516,000, but the number in the ‘retired’ category has actually fallen (see notes to editors for full breakdown);

• The number of ‘long-term sick’ has risen by over a third of a million (353,000) since the start of the Pandemic; this accounts for more than half of the growth in inactivity over that period;

• The rise in long-term sickness seems to be because more people are ‘flowing on’ to long-term sickness, particularly those previously classed as ‘short-term sick’; this could reflect NHS pressures as those who would otherwise have been treated or had their chronic condition better managed and able to work now find themselves ‘long-term sick’ as they wait for treatment or live permanently in poorer health;

• Numbers on sickness-related benefits have been rising steadily, with the growth pre-dating the Pandemic, but now worsening; although ESA is being (largely) phased out, the number of people in receipt for over five years has actually gone up in recent years and now stands at over 1 million;

The report proposes that the Government should look at a local level at data on benefit receipt and on NHS pressures to see if NHS bottlenecks mean that more people are getting stuck on sickness benefits and remain ‘economically inactive’ for longer. The report finds that existing statistics on elective waiting lists provide little clarity as they include large numbers of those over pension age waiting for treatment, and this would not directly help to explain trends in working age inactivity whereas data on GP pressures capturing waiting times for people with chronic conditions such as back pain, depression and diabetes could provide greater insight.

“There is a real risk of the government ‘barking up the wrong tree’ when it comes to the growth in economic inactivity.

”Commenting Steve Webb, partner at LCP said: “There is a real risk of the government ‘barking up the wrong tree’ when it comes to the growth in economic inactivity. Policy solutions which aim to reduce early retirement or to encourage the retired out of retirement are likely to have only limited effect in reversing recent trends. Instead, the policy effort needs to be focused around understanding why flows into long-term sickness have grown and on early intervention to prevent people’s health from deteriorating.

Without action there is a risk of a growing core of people stuck in long-term receipt of sickness benefits with limited prospect of returning to paid work and damaged prospects for retirement”.

“Without urgent and targeted research and action we risk a generation of working age adults with poorer health, employment and productivity as a lasting legacy of the pandemic”

Commenting, Dr Jonathan Pearson-Suttard, Head of Health Analytics at LCP said: “The pandemic made clear the links between health and economic prosperity yet policy does not yet invest in health to keeping living in better health for longer. NHS pressures have led to disruption of patient care from increased waiting times for routine surgery to less regular checks for those living with chronic diseases –all likely to be impacting people’s ability to work now and in the future. Joined up and local health and employment data could identify the link between ill-health and sickness benefits in sufficient detail to drive meaningful intervention to prevent this downward spiral. Without urgent and targeted research and action we risk a generation of working age adults with poorer health, employment and productivity as a lasting legacy of the pandemic.

Economic Inactivity amongst people of working age: a) before Pandemic, b) at time of Autumn Statement, c) latest data

|