By Richard Willets, Director of Longevity at Partnership

The Pensions Bill published in May confirmed that the UK state pension age,which was already set to increase to 66 by 2020, will step-up further to 67 by 2028. The UK is not the only country moving in this direction. A report produced in 2012 by the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) included the assertion that “67 is becoming the new 65.” Of the 34 member countries of the OECD, 13 have already moved to a state pension system where the retirement age was set to increase to 67 or higher.

Actuaries in the UK may therefore wonder to what extent the changes in life expectancy we have seen in this country have been mirrored in other countries. Furthermore, what can we learn about longevity trends by comparing the history of improvements around the globe?

The Human Mortality Database (HMD) maintained by Berkeley University and the Max Planck Institute is an excellent source of data on international mortality. 30 out of 34 member states of the OECD are represented.

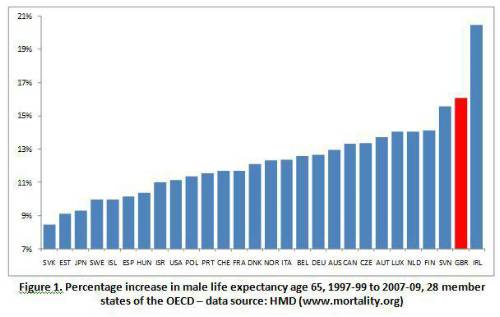

I used the HMD to calculate the percentage increase in life expectancy at 65 forOECD countries over successive periods of 10 years dating back to 1900 (with life expectancies averaged over three-year periods to smooth out some of the volatility). Most of the countries (28) have supplied data for 2009, so increases from 1997-99 to 2007-09 can be compared to get a feel for the latest improvements.

Recent increases in life expectancy for males aged 65 are illustrated by figure 1.

The UK ranks second out of 28 countries by this metric. In fact, the male life expectancy at age 65 in the UK jumped from being 16th highest in 1997-99 to 11th highest in 2007-09. This leap of 5 places exceeds that for any other country. Using this measure, the UK is the ‘highest climber’ in the longevity charts.

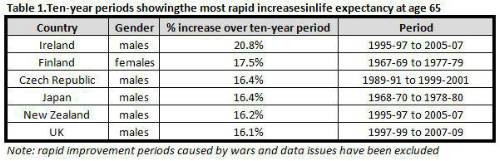

The improvement shown for men in Ireland is even more striking. To put it in historical context,having reviewed data on all the OECD countries in the dataset, the ten-year periods which have shown the most rapid improvements in life expectancy at age 65 (for either men or women) for any country are given in table 1.

The recent jump in life expectancy at age 65 in Ireland is easily the most significant increase we have seen in any country since the beginning of the 20th century. The period in question coincides with the ‘Celtic Tiger’ boom years. Ireland’s GDP grew by almost 10% p.a. over the period from 1995 to 2000 and then by roughly 5.5% p.a. up to 2007.

Finland experienced a period of rapid economic growth between 1967 and the mid-1970s and began the period with a low base for life expectancy at age 65. In 1967-69 life expectancy for Finnish females was just over 14 years; the lowest of all the OECD countries with data for that time.

The rapid improvement period for the Czech Republic coincided with its transition from a communist regime; the ‘Velvet Revolution’ took place in 1989 and Czechoslovakia dissolved into its constituent states in 1993.

Japan experienced its ‘EconomicMiracle’ in the post-war years with GDP growth running at approximately 10% p.a. during the 1960s and 5% p.a. in the 1970s. Furthermore, prior to the 1960s, Japan’s rate of stroke mortality was atypically high for the industrialised world, but began to drop precipitously from 1965 onwards. It has been argued this was due to interventions to reduce blood pressure levels and reduce salt intake.

New Zealand experienced an economic boom from 1993 onwards. GDP growth peaked at almost 7% p.a. in 1994 and then averaged approximately 3.5% p.a. for the period up to 2007.

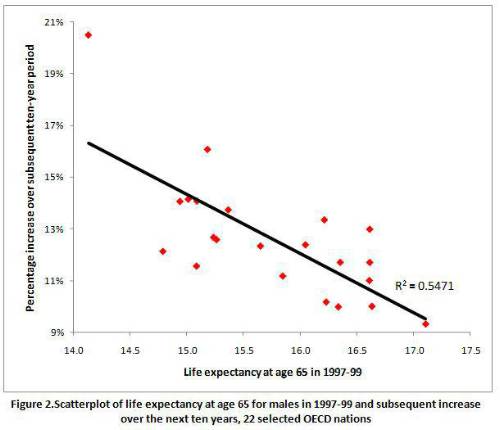

In general,it appears that periods of extremely rapid improvement in the life expectancy in particular countries,tend to coincide with periods of high economic growth. There also appears to be a link between atypically low life expectancy, or high mortality rates, and subsequent rapid improvement. Figure 2 shows that, if countries from Eastern Europe are excluded, there is an apparent negative correlation between the life expectancy at age 65 for males ten years ago and the subsequent rate of increase.

So, what does this brief look at international trends tell us?

First, we should recognise that the magnitude of recent improvements in the UK has been usually high; and only exceeded on rare occasions.Second, an analysis of the history of mortality change in other nations can help us to appreciate what factors may drive periods of rapid improvement in the future.

|