By Romek Matyszczyk, Director at Navigant

When one party seeks to trigger a buy-sell provision under a shareholders’ agreement, the valuation clauses, largely neglected since the agreement was drawn up, may hold many unintended consequences for both parties.

Shareholder agreements, or rather stakeholder agreements, are any agreements between the owners of an enterprise (and often the enterprise itself) that establish an ownership transfer mechanism in the event a shareholder wishes to, or is forced to, sell shares. Such agreements provide liquidity in the shares of private companies for which there would otherwise be no market. In many cases such arrangements provide that in the event a shareholder and the company cannot agree on a value, an independent valuer is appointed to determine value.

In most shareholder agreements, the valuer is called on to be an expert not an arbitrator. This has logic in as much as the valuation process is in place to provide finality and not prolong debate and discussion. Had the parties been able to agree there would be no need to resort to a valuation. However, an expert determination is generally considered to be one where the expert expresses their opinion of value without providing details or explanations as to how that conclusion was reached. This can sometimes cause bemusement and frustration for one or both parties if they are not aware that the result of the valuation process will be a one line opinion of value. We have seen provisions that provide for a reasoned opinion of value. Some valuers may not accept such instructions and those that will, may require indemnities.

The value of a share interest generally changes over time. Sometimes even small time differences can cause large swings in value. It is, therefore, critical that there is no ambiguity as to the date of valuation. Corresponding to the selection of valuation date are assumptions made about the date at which the shares are assumed to be transferred, and the payment of any interest from that date if the shares are not transferred.

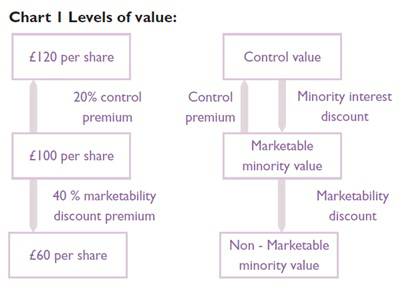

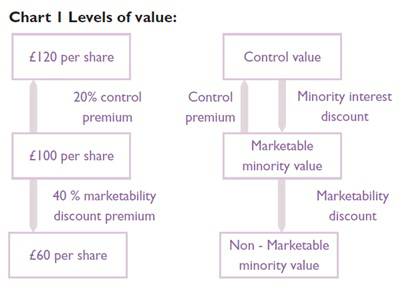

The term ‘value’ is not ubiquitous. Modifiers such as ‘market’ or ‘fair’ are generally added. Each of these modifiers provides a different connotation to the term ‘value’ from a professional valuer’s perspective and produces different results. There is no such thing as ‘the value’ for the shares in a closely held company. Even if there is no change in the underlying business value, share value can change according to whether allowance is made for strategic benefits, marketability, and control. Chart 1 demonstrates the importance of carefully defining the appropriate level of value – the difference in share value can be dramatic depending on the assumptions made.

Note: all percentages referred to above are for illustration purposes only and not intended to convey that such percentages are to be used in every case. Facts and circumstances of each case will dictate whether or not premiums or discounts are appropriate and their quantum.

The valuation process refers to the actual conduct of the valuation, the provision of information, the timetable and the costs. While most agreements provide for a single valuer to be appointed, we have seen those that provide for two valuers, one appointed by each party and a third valuer to adjudicate in the event the first two disagree or disagree by more than a certain percentage, say 10%. There are benefits or attractions to each side appointing its own valuer, but this must be balanced by the cost of such an arrangement. The provision of information can also be a problem area. The reality is that most, if not all, information will be provided by the company or the entity whose shares are being valued. However, when there is a degree of hostility between the parties, what information is provided to the valuer, and by whom, can become an issue. This problem can be addressed by specifying in the agreement that the valuer must take one or more representations from each party or by questioning potential valuers as to their practice in regard to information gathering.

It can be very tempting to include a formula by which value is determined. There is a belief that this provides a measure of certainty of outcome. While a greater degree of certainty of outcome may result, the value conclusion that is reached based on a prescriptive formula may bear no relationship to reality. As referred to previously, value changes with time, so a formula designed thirty years ago using what may have been appropriate multiples at that time is unlikely to still be relevant.

The nature of valuations as opinion based on art more than science, combined with the usual desires of the buyer to pay a low value and the seller to realise a high value, means there may always be some dissatisfaction with any valuation conclusion. In our view, the ideal outcome is when both buyer and seller are satisfied with the valuation. Or, if not, they are at least satisfied the process undertaken to reach that opinion was fair. We think this can be achieved by the parties seeking to reach agreement on as many aspects on the future transaction as possible, including a valuation process relevant to the circumstances, and the valuation elements relevant to that process.

Poorly drafted or misunderstood valuation clauses in buy-sell agreements are potentially a ‘ticking time bomb’ for the parties to such agreements. In our view, risks can be minimised for the parties if a clear understanding of the terms of reference for the valuer and the valuation process are reached and reflected in the drafting of the valuation clauses. Shareholder agreements are often neglected once signed. We suggest that such agreements are reviewed periodically to ensure that the valuation clauses will deliver the kind of result contemplated by the parties on signing and, if not, then the clauses be modified as appropriate. Remember, value changes with time and an ounce of prevention in modifying valuation clauses, is far better and cheaper, than a pound of cure, when dealing with the consequences of clauses that are no longer, or never were, relevant.

|