By Alex White, Head of ALM Research at Redington

Corporate DB schemes typically need to pay long-dated inflation-linked cashflows, so (via LDI programs and with leverage) they buy long-dated inflation-linked bonds. In a DB context, inflation protection has a clearly defined meaning, and the basic solution flows from that.

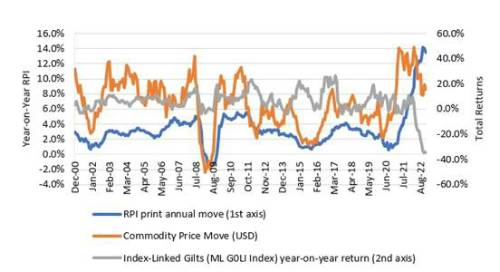

In contrast, it’s much less straightforward in the retail market. If a retail investor buys a portfolio of “safe” government bonds that offer inflation linkage, they may expect performance in inflationary environments. However, because of the overwhelming impact of interest rates and their relationship with inflation, linkers can often do the opposite. In 2022, for instance, inflation was 13% while linkers fell in value by over 34% (see chart below).

And this is the crux of it - inflation protection can mean at least two different things, which will motivate different solutions. It can mean protecting against short-term pricing shocks, or protecting against long-term real income depreciation. By way of illustration, prices can go up 10% next week then plateau, or they can go up by 1% more than expected each year for 20 years. These factors can be very different, as will the investments available to meet these goals: 20y RPI swap prices only have a c. 30% correlation with 1y RPI, for example. So it’s worth delving a little into how defining the goals might change the portfolio you end up with.

Protecting against shocks

In the first case, short-term shocks impact the amount of money an investor may need upfront. So assets that do well in inflationary shocks, such as commodities or trend-following strategies, could be appropriate investments. On the other hand, inflation-linked bonds, equities (which tend to fall during inflationary shocks such as the 1970s or 2022), and illiquid assets (whose prices move slowly), would not achieve this goal and are more likely to see their prices fall in the short term.

Protecting against sustained high inflation

To protect against long-term income, the options are a little wider. Inflation-linked bond prices are, in a very literal sense, the cost of inflation-linked cashflows. These could represent a good asset to “lock in” current prices and reduce the risk that value is eroded by high inflation through time. However, for investors who are limited in their use of leverage, they may not offer high enough returns.

Over the long term, equities are a good asset for beating inflation, for two reasons. Firstly, they can often pass through rising costs into rising prices; but also they just tend to make money at a greater rate than most other viable options. For investors who can afford to take short-term risks, equities are often a great investment- they have a clear economic rationale for why they work (companies produce stuff), and a long, well-evidenced track record. Similarly, where investors can afford to tie up their money and a sufficient illiquidity premium is available, illiquid assets can also be appropriate.

At the same time, trend strategies are likely to deliver long-term returns, should hold up well during shocks, and are relatively neutral to sustained inflation. If inflation is 4% p.a. for 20 years instead of 2%, that could be a good or bad period for trend, with no clear case either way. And while commodities generally offer protection against inflation shocks, over the long term they have been very volatile with a low Sharpe ratio, weaker risk-adjusted performance, and weaker ESG characteristics. So they may not solve the longer-term problem.

So what portfolio should you hold to protect against inflation?

Well, it depends. The assets that work for each of these goals aren’t the ones you’d choose to solve the other. In some cases, they could have a negative impact. Which assets you choose to protect against inflation depends, in large part, on working out precisely what you want to be protected from. And if you want both, and a portfolio that meets multiple goals, then it’s hard to do better than a well-diversified portfolio.

|