By Alex White, Head of ALM Research at Redington

From the regulator’s perspective too, it must be easier to regulate 1 large scheme than thousands of small ones. Moreover, the typical risk of any form of consolidation in general is that risks become more concentrated; with pension funds the opposite may be true, as the smaller schemes are likely to be forced into similar asset strategies while the larger scheme can hold a more diversified portfolio.

However, thinking purely about economies of scale misses one of the bigger advantages, which is idiosyncratic longevity risk.

To explain this - a pension fund has longevity risk because, if members live longer, the scheme has to pay more. There are basically two way this can have an impact- either everyone lives longer (longevity trend risk), or the individuals in a given scheme happen to live much longer than their peers (idiosyncratic risk). Trend risk affects everyone equally- all schemes, regardless of size, run the same risk. Idiosyncratic risk is different however.

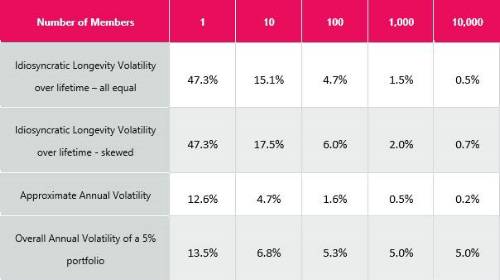

As a simple calibration, we looked at the cost of a 65-year-old man getting an inflation-linked annuity of £1 a year, using CMI 2019 tables and an improvement factor of 1.5%, and discounting at gilts + 50bps. We then simulated the realised present value (PV) if he dies at different ages (with the probabilities given by the mortality table). We then repeat this to get 10,000 simulations of 10,000 people, and calculate the volatility of aggregated PVs of future cashflows for different numbers of members. We show this both for the simple case where every member has the same pension, and for a more realistic case where the values are skewed (we used a logarithmic based on UK income statistics, such that for any group of members, the top 20% of members account for 40% of the total value).

Finally, we considered what impact this might have on a hedged scheme with 5% volatility from other sources (roughly equivalent to a 25% equity, 75% LDI portfolio including longevity trend risk). To do this, we approximated an annual volatility by scaling down by the square root of the duration, just to get a comparable number.

As you can see, the risks are quite large.

As the above example shows, simply consolidating 100 ten-member schemes into a single thousand-member scheme could reduce overall risk to members by over 25%, without doing anything else.

Members who would have been paid full pensions in a larger scheme could end up out of pocket in their later years when their opportunity to do anything about it is smallest (while other funds would see a positive return from their previous employees dying faster than expected). When thinking about how to make consolidation work, it’s worth realising that the bar for it to be an improvement over the current system might be quite low.

As a final thought, the most extreme case is the single member case, which is what every DC scheme member faces. This is a meaningful risk faced by individuals, and it can be diversified away in any sort of pooled structure. It should not be hard for a CDC scheme to be better for members than DC – something perhaps worth a future post of its own…

|