This figure is made up of:

- Income tax relief +£46.8 billion

- PLUS National Insurance relief +£23.8 billion

- MINUS income tax on pensions in payment -£22.0 billion

NET cost of pension tax relief +£48.7 billion

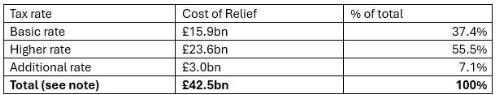

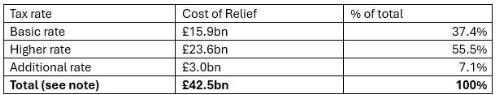

The statistics highlight the extent to which the cost of income tax relief is skewed towards the highest earners, who tend to pay more into pensions than lower earners and who also benefit more because they get relief at their marginal rate of tax. The table shows how the total cost of income tax relief is broken down according to whether the saver pays income tax at the basic/higher/additional rate.

Source: Author’s calculations based on HMRC ‘Table 6’

Source: Author’s calculations based on HMRC ‘Table 6’

Note: The total of £42.5bn in this table is the £46.8bn cost of income tax relief shown above but excluding £4.3bn for the income tax relief as money grows inside a pension which cannot be easily attributed to individuals.

The key point about this table is that well over half of all pension tax relief (62.6%) is enjoyed by the highest earners. On the face of it, it could be attractive to a Chancellor keen on redistribution to find ways of cutting the benefits enjoyed by the highest earners and raise significant revenue in the process.

However, the same statistics provide some indication as to why this is likely to be difficult in practice. Out of the total of £42.5bn in relief allocated to individuals, nearly half - £19.7 billion – is on contributions made into Defined Benefit pension schemes, particularly those in the public sector.

Cutting tax relief on these schemes raises several problems for the government:

- The main losers will be senior public servants, often in highly unionised sectors; given issues around public sector pay and ongoing pay disputes, it seems highly unlikely that the government will want to alienate this group;

- Cutting tax relief on employer contributions in a public sector scheme either means increased costs for public sector employers (such as hospitals and schools) or would be passed on to employees creating large tax bills on contributions which they may not see the benefit of for years to come;

One possibility is that the Government could decide to leave Defined Benefit schemes alone and focus on the remaining £22.7bn of relief to modern Defined Contribution or ‘pot of money’ pensions. However, if all the additional revenue was raised from this group this could aggravate concerns over a ‘two tier’ pension system with public sector workers being protected from tax rises.

As a result, the Chancellor may ditch more radical ideas such as applying ‘flat rate’ tax relief on pension contributions, and instead try to find other ways of cutting the tax breaks to those with the largest pensions. For example, today’s figures show that the previous ‘Lifetime Allowance’ (LTA) generated charges of £516m for the government in 2022/23, before the rate was set at 0% by Jeremy Hunt in 2023/24 and the LTA abolished in 2024/25. The new Chancellor may be very tempted by a figure of this magnitude to look for a way of reintroducing a lifetime limit of some sort.

Commenting, Steve Webb, partner at consultants LCP said: “There is no doubt that the Chancellor will be eyeing up the large price tag attached to providing tax and National Insurance relief on pension contributions. This is particularly the case when more than 60% of the cost of tax relief goes to those paying tax at the higher or additional rate. But raiding this pot is far from straightforward, particularly in the case of Defined Benefit pension schemes. It may well be that the new Chancellor ends up where previous Chancellors have ended up, namely finding complex technical ways to claw back reliefs from the wealthiest but leaving the majority of savers unaffected”.

|