Perhaps surprisingly, fewer arguments seem to have been raised against other struggling premia, such as EM (a simple long MSCI EM, short MSCI World strategy would be down 48% from 2010, and down further on a beta-adjusted basis), or commodities (excess returns down 71% since 2008). This may be because those premia are more intuitive. However, it’s difficult to see why value - at least sector -neutralised value - would never work. While the likes of Amazon, Apple and Microsoft have clear business models, the economy would not work if all companies were set up like, say, Uber. Individual companies can thrive from growth in their multiples, but at an aggregate level it’s hard to avoid the conclusion that the value in equities is driven by creation. More prosaically, we can’t all be start-ups, and some companies have to make money. If all $60bn firms posted $3bn losses each quarter, something would have to give. At that extreme point, profitable companies should outperform loss-makers. Of course, we may be a long way away from that, and value may still fall further.

One difficulty is that, if value does still work, even if it’s weaker than before, then the spreads in valuations are much wider because it’s underperformed. That is, cheap companies have underperformed expensive companies and are now cheaper, while more expensive companies are now even more so.

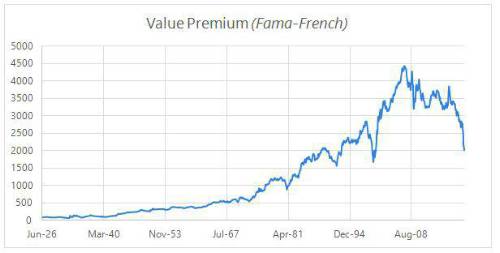

Over the very long-term value has performed, with a 3.2% log return, 12% volatility, and a p-value of 0.9% of having a positive mean return. However, it’s possible that the world has changed. AQR are hardly neutral observers, but have put out some excellent pieces addressing some of the specific arguments against value. Rather than duplicating that, I’ll approach this from a slightly different angle.

The primary driver for a lot of these theories is value’s underperformance. This is valid, as new evidence should change your opinions. However, it falls victim to the Texas sharpshooter fallacy. If I fire a rifle at a target and hit the bullseye 3 times in a row, that’s impressive; if I fire a machine gun and 3 of the many bullets hit the bullseye, that’s less impressive. Similarly, with plenty of risk premia available, what is the probability of getting underperformance like this?

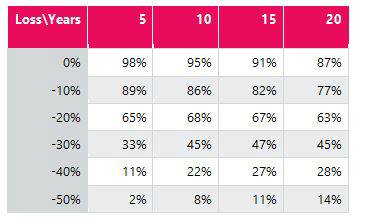

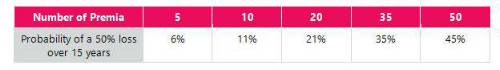

To answer, we simulate a number of uncorrelated risk premia with 12% volatility (in line with the value premium), and assume a modest but worthwhile 0.2 Sharpe. The first table below shows the probability of at least one asset losing at least x% over n years, assuming 10 risk premia. The second shows the chance of losing at least 50% over 15 years for different numbers of risk premia.

Even if you only believe in 5 risk premia across all markets, it’s still not that unlikely. Crucially too, this is picking a random time period or fixed length, not the worst period of the worst length from a longer history, so there’s more bias in the history even against these figures.

The key point is, even if all your risk premia are intrinsically valid, some of them will fail, and some are likely to fail badly over a prolonged period. The explanation for value’s underperformance may simply be noise - that risk premia sometimes underperform.

As long as you have a balanced, diversified portfolio, some strategies will struggle. The price of a robust portfolio is that at any point, some parts of it will be underperforming.

|